In the summer of 2006 I visited Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England. Before heading overseas, I arranged with the English Heritage Society to have a pre-dawn hour at Stonehenge, which cost just 25£. It was dark when I arrived before 5 a.m., after the 39-mile drive down from Somerset, where I had been staying. I found myself in a small parking lot that lay on the other side of a highway running past the ancient megalith. A park ranger was in an office that lay beneath the road, but for a while I thought no one was there and that I’d not get in at all. To this day I don’t know if he was there just for me or if he was on the night shift, guarding the place. He directed me through a tunnel that ran under the highway and under a fence. I went up some stairs in the dark and stepped out into Stonehenge.

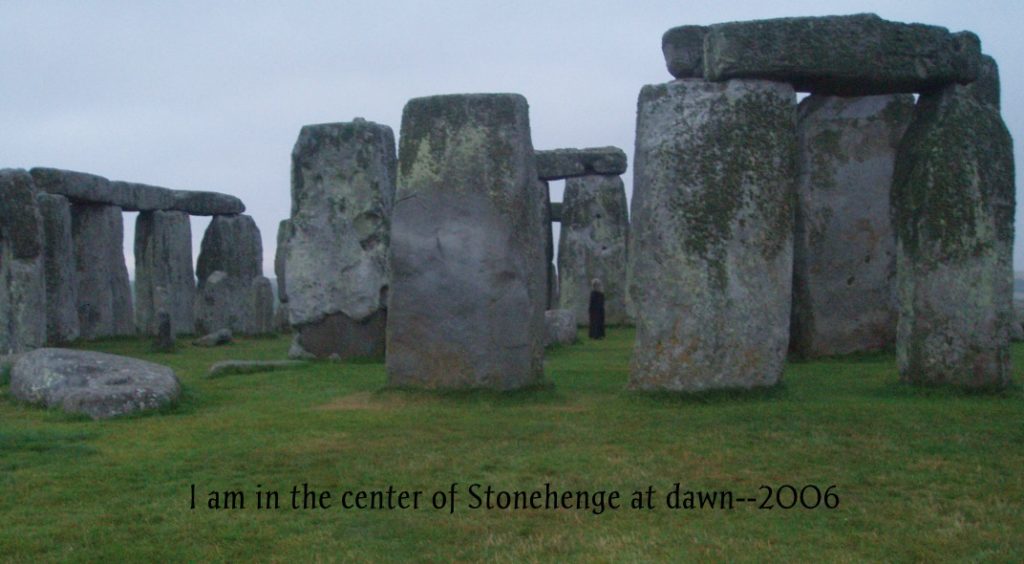

I had the hour to myself. The person who had driven me down had been there, done that, he said, and so he stayed outside the circle, though he took several photos, like the ones shown here.

I moved among the stones, touching each one, aware of nothing else. It was a time of no thought. I felt an energy and power I absorbed but had no words to explain, nor wanted any.

I left England a week later and did not return for two years. I’ll write of that 2008 visit in another post, for then I visited other ancient stones, including Avebury, and that set in motion a major shift in perception. But the experience in Stonehenge was the catalyst that drew me back.

Stonehenge and Prehistoric Britain

Over six thousand years ago the people in Britain created massive monuments and stone circles and dolmens and passage graves, all to honor their dead. We don’t know how they did it without technology and with only stone tools. What did they use to lift tons of stone blocks and lay them upon other stones in the circle? What ceremonies did they perform then, and why? Such mystery rises out of that time. It is a wonder with the many invasions of Britain by the Romans, by marauders like the Vikings, by Germanic tribes, by the Normans–the endless trail of men seeking to own other men and land–yet these monuments stayed far more intact than seems possible.

They are magnificent. They are more than signs from the past. In their presence, we change.