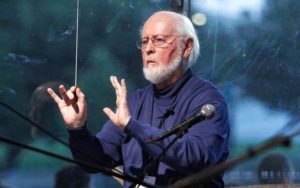

It’s understood that music enhances films, and no one has done that better than John Williams. But as I listen to his compositions, I wonder sometimes whether in fact his music does much more. Perhaps sometimes his music is the primary reason the film succeeds.

The common cliche is that all filmmaking is a collaborative process, so I wager Williams would be the first to deny the possibility his music alters anything. He’s written so many scores, including the scores for Star Wars, Home, Alone!, E.T., Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Jurassic Park, Superman, Harry Potter–movies I adore.

But I find if I mute the score when I’m watching those films, something seriously changes. It is as if the heart of the film is absent. Not just its emotional feeling tone, but the reason I’m watching.

The Music Is Telling the Story…

Williams’ music creates the story at a level we can’t resist:

- “Luke’s Theme” plays as young Skywalker looks out at the discs of two suns–it is the notes we hear that reveal Luke’s yearning–a haunting, unforgettable image.

- The neighborhood filled with Christmas lights as the camera zooms in becomes enchanted with the synth chimes and celeste, the woodwinds and sleigh bells that Williams gives to the opening of Home, Alone! He used the celeste again in the first Harry Potter film as “Hedwig’s Theme.” Who doesn’t want to enter a magical world like these two musical openings promise? (I remember a television ad appearing before the first film was released playing this theme as it showed the snowy owl Hedwig tracking to a bookstore–it pulled one in like a magnet.)

- In Superman, there is marvelous thematic music, but underlying it also is something in the music itself that offers a sense of the unknown, of the immense mythology of the franchise, its origins back in the 30s, and the entry into a world that has such a wonderful being in it, our own mystical yearning for that kind of goodness.

His Music IS Storytelling

In these movies, as in the others he scored for, including Schindler’s List, I can’t separate the music from the film itself. Without the music, the movie loses more of its meaning. What Williams has created does define the experience of watching the story. His music is storytelling. It can’t be left out.

As in Star Wars…

I remember in an interview George Lucas said that on the opening night of Star Wars he and his wife Marcia went out to get something to eat in L.A., and were astonished to see a mob of people across the street and a line around the block. He wondered why and suddenly realized it was to see Star Wars. He hadn’t expected such response. He felt it was a film he hadn’t been able to shape in its full potential, that he lacked the technical devices he needed to make it better.

I remember watching it in a theater in New York City, in Times Square, a few days after its release, and taking my three-year old son with me, and both of us sat mesmerized along with the rest of the world by the opening credits made colossal by Williams’ extraordinary music as the story began to unfold. Imagine that opening scene without that remarkable score. If for Lucas the technical aspects were not what he had dreamed of, Williams’ music made the entire movie a riveting, totally absorbing and emotional experience.

A Truly American Composer

He wrote symphonic themes, too, that were so essentially, blazingly American, defining the films that way. I remember hearing him conduct his original music for the film The Reivers. It held in it the same contours of folk melodies attached to the American landscape that appeared with Aaron Copland’s exquisite music in “Appalachian Spring” and “The Red Pony,” or Virgil Thomson’s “The Plow That Broke the Plains” for the documentary on the Dust Bowl. Williams is a true artist, and how fortunate we are he brought that same classical tradition into the movies.

And how fortunate that insightful directors asked him to write his brilliant music for their films. So he did in ways that ensured the characters and their stories would forever be part of our hearts, and often, part of our souls.