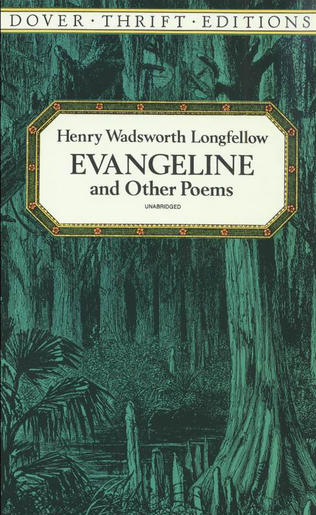

“THIS is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.”

These words open Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Evangeline, published in 1847.

I have heard this poem since childhood, read aloud to me by my father and read also in school often. The sometimes archaic expressions did not phase us back then–we understood the idea was that we were meant to feel the words when we listened.

Living in the Maine Woods in Early America

Although Longfellow tells the true story in this poem of a place called Acadie and the expulsion of the French from Nova Scotia by the British, separating two lovers, these opening words are an image from his home near the coast of Maine, at a time when the pristine wilderness in America still existed much as it had before the invasion of the Europeans in the early 1600s. This aspect carried great meaning to his contemporary audience, for the book went through six printings in its first six months and was received with enthusiasm internationally.

Why? It was more than the story. In the setting he gives, we are delivered into a region that existed much as it had for millennia, that had never until now been explored, that was still a symbol of the frontier to many, though soon that frontier would encompass the west at a furious pace. And it was a place also experiencing the encroachment of the foreign invasion–faster than could be dreamed.

An American Enigma

There is a curious contradiction in the American mindset, a two-sided vision of our reality. On the one hand is our materialism, our sense of ownership of the land and everything on it, there for the taking. On the other is awe, something embedded in us by the poets and artists and writers and painters and composers who have from the beginning attempted to explain this vast landscape in symbols of their own, an awe that at its source reveals a deep love and reverence for the incomprehensible beauty and gift of the earth we live on, of this wilderness we have entered.

We have so far tended to learn only one side of that contradiction, the hunt and grab one.

Yet we are not bereft of the other side, the awe and acknowledgment of this wondrous land. It is still there to know.

God willing we keep it so.