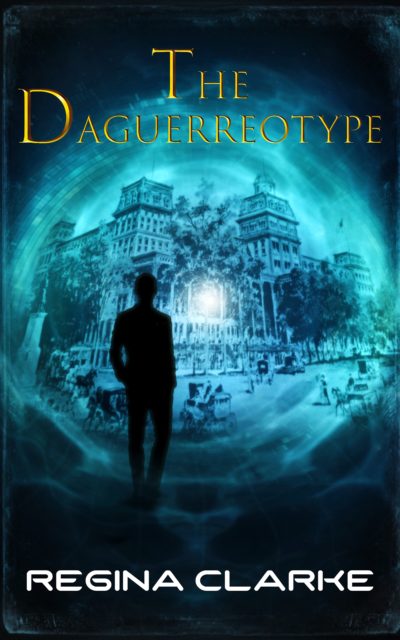

The Daguerreotype

Available at: Amazon Kobo Barnes & Noble iBooks - Apple

The daguerreotype–hallucination, or reality?

Browsing in an old shop, Professor Harry Inman comes across the image of a famous hotel in Saratoga Springs, NY, taken on a fragile metal plate in 1847, an actual daguerreotype from the origins of early photography. The small framed image becomes an unexpected window into the past, one that pulls him into another time and space.

It is a world that appears increasingly mesmerizing and seductive, the Saratoga Springs of grand hotels and Victorian glamour, of people strolling in summer along tree-lined boulevards that no longer exist. The music he hears enchants him. Each visit brings him welcome release from the stress and dullness of his ordinary life. Most startling, on one such visit Harry encounters the man who created the daguerreotype in the first place–who acknowledges Harry as if he knows him. How?

He doesn’t have time to ask. His visits are only brief ones, and the daguerreotype, already corrupted, is fading. He must make a decision before the image disappears.

Excerpt:

He studied the plate a few moments before reaching into the top drawer and taking out a magnifying glass, but hesitated before applying it to the image. What would he see this time? The caption printed in old script called it a view of the Grand Union Hotel, Saratoga Springs, New York, 1847. The artist’s name embossed in gold leaf on the frame was too worn to read, though at times he thought it might be Samuel Morse, but that was just wishful speculation. Morse had introduced the daguerreotype to the country around 1840 from his residence in New York, instructing Matthew Brady, among others. The Meade Brothers were well-known daguerreotypists who had established themselves in Saratoga Springs for a while. Itinerant practitioners flourished in the U.S. after that. The image could have been made by any one of them.

With a sigh he bent close to the scene that showed itself. He knew the history of the hotel, or at least what online data could tell him. In its heyday it had over a thousand rooms and entertained royalty and politicians, literary figures, and the wealthy elite. The mineral springs nearby with their healing elements drew crowds in the summer. Ornate arched columns fronted the place. The dining room alone was over two hundred feet long, filled with frescoes and mirrors.

The depth of detail was the trick–the magic–of the daguerreotype. He could zoom into one indefinitely, it seemed to him, no blocks of pixilation ending entrance into the image, but rather allowing him to explore the details as if he were detecting an infinite universe. No modern photograph could come close to that.

What wasn’t possible was to have the sight of well-dressed people walking under the massive elm trees near the entrance and of horse carriages passing along the Broadway that was one of the busiest streets in the small city. Stillness was required for these early images to present themselves. Exposure times had been reduced from hours to minutes to seconds, but even then, anything that moved would have a ghost image attached. Should have…

Book categories: Mystery, Science Fiction, and Time Travel